How do I draw a dog that looks real? As young aspiring artists, students often ask questions like this because they measure their success and growth in art based on how real they can make something look. Recently, my seventh-grade students discovered that artists possess many tools to draw the viewer in and gain appreciation for their art. And, these strategies can be much more powerful and exciting than realism.

Before beginning seventh grade, students end sixth grade studying Realism, the first modern art movement focused on realistically portraying real people in their everyday lifestyles and pursuits. This will be the last time students see realistic artwork until the very end of the seventh-grade curriculum when they study photorealism, where artworks look as glossy and realistic as a photo.

The seventh-grade art curriculum is one of my favorites, partially because of the numerous art movements and many prominent artists that emerged in just under a century, from 1865 with the beginnings of Impressionism to the 1950s with the explosion of Abstract Expressionism. However, the story that encompasses this time frame is even more consequential.

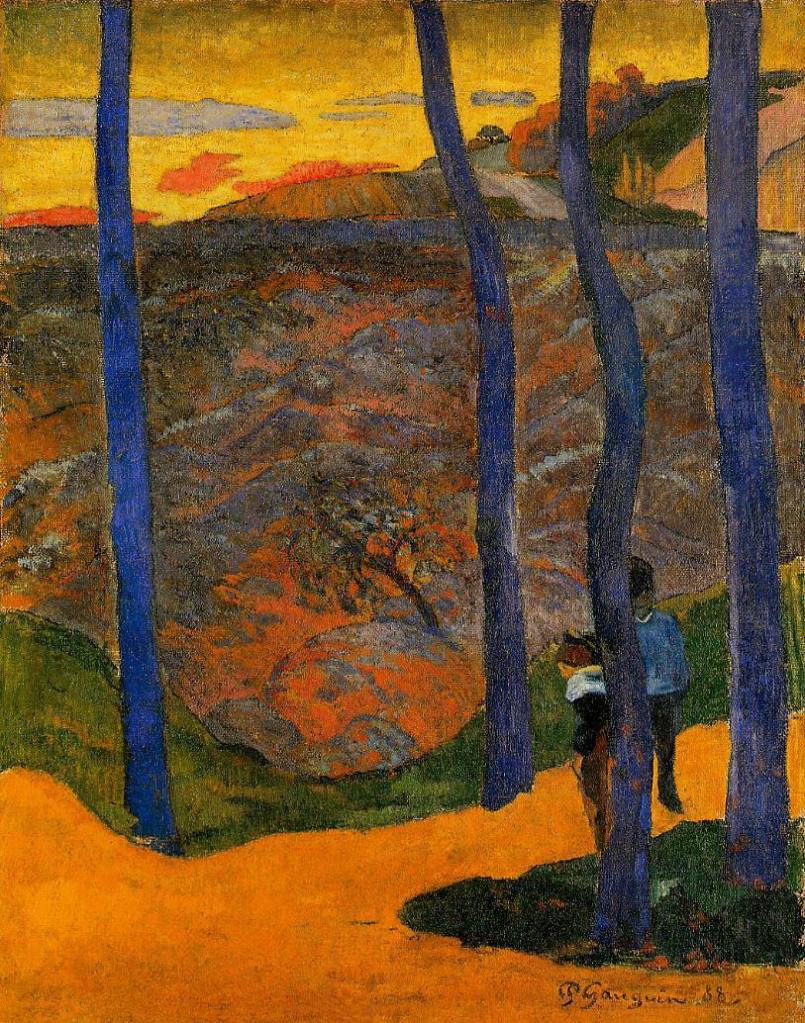

As the seventh-grade curriculum unfolds, students explore Impressionism, a movement focused on color and the optical effects of light where artists attempted to convey the fleeting nature of atmospheric conditions. As the name suggests, Impressionist artists aimed to capture only an “impression” of what is real and concentrated on the world as they saw it, continuously changing and imperfect. Next, students explore the diverse styles of art proposed by the Post-Impressionist movement. While moving away from Impressionism, artists still explored the effects of color, such as Gauguin’s powerful usage of complimentary colored shapes to make bold compositions. However, artists like Cezanne employed exchanges between color and shape to describe the world in his art. Finally, students study Neo-Impressionism, a movement that relied on the viewer’s ability to optically blend dots of pure color on a canvas to make the distinct strokes come together in a convincing and ever-changing image. Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte is a prime example of this pointillist method. This method can also be described by the word “divisionism” because these artists were dividing their artwork into small dots and relying on the arrangement of those dots along with the viewers’ ability to visualize the whole image.

Of all the art methods my students explored this semester including plein air painting, impasto painting, linear movement and shapeliness, my students’ favorite way to create art was pointillism! How could a series of dots be so inspirational to students who once thought making things look as real as possible was most important? Well, I think my students were impressed by the pointillists’ ability to draw in and challenge the viewer and excited by the opportunity to practice a type of scientific art in optical mixing. There was certainly a magnetic and mystical aspect to this form of artmaking!

As students finished their first semester, I asked them to chronologically organize artworks from the time periods they studied and explain what the artists were prioritizing and how their styles changed. The students were shocked to discover that the artists were continually moving away from making paintings that looked real and were instead focusing on highlighting basic elements (color, line, shape, form, value space, texture) and arrangement. Essentially, their art was becoming more and more abstract, moving toward non-recognizable subject matter. However, the students were quick to admit that, overall, these more “abstract” works did not lose their emotional appeal, intrigue or painterly qualities. In fact, freeing oneself from “the real” allowed for expression and individuality on the part of artists. Our aspiring artists who realize that copying something perfectly is not always necessary and embrace creativity and their own gifts and interests can yield something even more inspirational. In the words of Seurat, “I painted like that because I wanted to get through to something new – a kind of painting that was my own.”